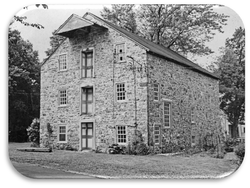

Laudenslager's Mill

Laudenslager's Mill

Manufactures in 1810

by Greg Huber

(This article was published in Fall 2013 LMTHS Newsletter)

Within the archives of the Lehigh County Historical Society is a document called “Manufactures.” The number of occupations listed reflects a countywide economy that concerned itself essentially with local markets. The products manufactured then tell of a local populace that was thriving in the very early part of the nineteenth century.

This was the era just before the advent of what historians have called the “market revolution” in the 1815 to 1840 timeframe. The 1810 list bespeaks a time when people in our area were producing goods using hand-forged tools in time-honored fashions since the mid-eighteenth century.

The list of trades and crafts is far beyond the commonly known occupations of farming, milling, masonry and weaving. Hundreds of people in the county then worked in a number of areas of employment. In earning their livelihoods, they formed an important part of the vast network of people working for and attending to the needs and desires of county residents. The list is not complete: a number of manufacturing occupations are not listed in the 1810 list, but can be found in, for example, early tax lists from Allentown. A surprising omission is the then-famous gun works in Jacobsburg.

The document is part of the population census of 1810 in Northampton County. This was two years before the western part of the county broke off and became Lehigh County in March 1812. The census consists of several pages of information, including areas of production called “manufac-tures,” with proprietors’ names, the amount of product of each activity, and the amount of money each proprietor made in the year 1810. All nineteen occupations are listed below, with the numbers of each and the total quantity of the product created by all the proprietors in each category, along with a few comments. The total number of proprietors was 318. Farming was not included. The number of farmers was likely in the thousands.

Grist Mills – 63 – 6,850 barrels of flower (flour) and 250,000 bushels of grain. Wheat flour was a cash crop for farmers. In 1810 the most common financial arrangement farmers had with millers was to pay for the miller’s work with a portion of the milled grain. A few gristmills built before 1810 in the area retain at least some of their original machinery. In Lower Macungie, the 1806 Kohler mill on Farr Road is an example.

Saw Mills – 27 – 970,000 feet of board and scantling. (Scantling is small timber used in construction.) Most timber processed by the sawmills originated from first-growth or virgin forests in the greater Northampton County area. Some may have come from secondary-growth sources or also perhaps from sources outside the county.

Paper Mills – 1 – 1,200 rheams (reams) of paper. A ream contained 480 sheets of paper then.

Oil Mills – 4 – 3,000 gallons of linseed oil – Linseed oil is a yellow oil extracted from the seeds of flax and used in paints and varnishes. It is possible that David Deschler’s stone structure on Orchard Place in Lower Macungie, known later as Seem’s Mill, was built as an oil mill. Another oil mill of eighteenth-century vintage was on Mill Race Road in Lower Macungie behind the 1832 Neumeyer grist mill.

Fulling Mills – 1 – unknown product quantity. Fulling is a water-intensive step in making cloth. It involves cleansing woven woolen cloth to eliminate oils, dirt, and other impurities, then pounding the fabric. The process shrank the fabric and made it thicker and softer.

Carding Machines by Water – 6 – 15,625 units of wool. Carding was a process by which fibers were opened, cleaned, and straightened in preparation for spinning. Modern carding dates from the use of revolving cylinders patented in 1748. Much carding would still have been done using hand tools in the home, and was not included in the industrial category.

Trip-hammers – 1 – 30 tons of iron. A trip hammer is a massive, usually water-powered hammer. The use of this one was not specified.

Distilleries – 100 – 105,170 gallons of rye and apple whiskey. It is not surprising that distilleries are by far the most numerous manufacture on this list. David Schmoyer is known to have operated an applejack distillery in Lower Macungie near Spring Creek and Route 100 from 1799 to 1801.

Tobacco factories – 6 – 30 tons of tobacco. Snuff, cigars and smoking and chewing tobacco were popular products at the time.

Potteries – 3 – unknown quantity. Local clays were used to make earthenware items in potteries.

Weavers – 45 – 70 looms and 47,000 yards of product. The list does not specify the type of cloth made. Some would have been linen, and some wool. Most farmers in Northampton County raised sheep for wool and meat, and grew flax, from which linen is made. Linen was used for fine textiles, work clothing and sacking. It was often used as the warp thread with wool as the weft thread to produce a strong, warm fabric.

Smitheries – 22 – 56½ tons of iron. Of all the manufactures listed here, the work of the smith was likely the most important as all farmers and probably all of the other occupations ultimately depended on the smith. Smiths made and repaired iron tools and farm and household implements of every description, and shoed horses.

Bluedyers – 3 – unknown quantity. Today these would simply be called dyers. Thread was usually dyed before being woven, using natural dyes derived primarily from plants.

Printing Offices – 1 – used 300 rheams (reams) of paper.

Hatters – 6 – 1,750 wool and 1,120 furr (fur) hats. Hatters made, sold and repaired hats.

Blast Furnace – 1 – 300 tons of iron – Hampton Furnace was built in 1809 in Upper Milford Township. It was a charcoal-fueled furnace.

Saddlers – 3 – unknown quantity. Saddlers made not only saddles for riding horses, but any kind of harness needed on farms and in towns.

Shoemakers – 20 – about 380 pairs of boots and 4,400 pairs of shoes. Most families made their own shoes.

Lime kilns – 5 – 12,000 bushels of lime. See pages 104–107 of A History of Lower Macungie Township. Burnt lime was used in construction, and was spread on fields. The five lime kilns listed were most likely large operations that provided construction material. Most farms in the limestone valley had a small lime kiln for their own use. Large commercial kilns were built later; one row may still be seen at Lower Macungie Township’s Camp Olympic Park.

Population

The 1810 document includes the population of residents of various townships in Northampton County. After Whitehall Township (which then included today’s Whitehall, South Whitehall and North Whitehall), the most densely populated area in all of Northampton County was Macungy Township. The census accounted for free white males and free white females. The total population for Macungy then was 2,431 males and females; one slave was listed, associated with the name of Reverend Jacob Van Buskirk, pastor of Lehigh (Zion’s) Lutheran Church in Lower Macungie. Van Buskirk owned a tannery in Macungie, which he founded in the mid-1780s.

All the occupations listed above are not found in all of the townships. Based on the extensive population of Macungy in 1810, the township had to have included at least six of the occupations. They include gristmills, saw mills, distilleries, weavers, smitheries and shoemakers. One tannery existed but was not listed. Residents of the township also pursued other occupations.

One interesting case of an occupation assigned to an individual but lacking a designation to a place of residency is that of John Romich. His name is listed as a gristmill owner. He produced 10,000 bushels. Romich was more successful (produced more bushels) than 60 of the 63 listed gristmill owners. A strong indication that this Romich family member occupied an area in Macungy is the mention of Romig’s Mill in A History of Lower Macungie Township (page 133), which states that “the locale surrounding the mill was once so thick with Romigs that for many years it was known as ‘Romig’s settlement.’ ”

Summary

The manufactures list of 1810 proves that many occupations existed in Northampton County at the end of the first decade of the nineteenth century. The structures themselves, unfortunately, associated with most of the manufactures have disappeared from the landscape. Exceptions include a few grist mills including the 1806 Kohler mill in Lower Macungie and a few lime kilns scattered about the countryside. In addition, several of the buildings in the Moravian industrial quarter established in the eighteenth century along the Monocacy still stand; they were presumably included in the tallies.

In 1810, the then prevailing technologies of production created hand crafted, non-standardized consumer goods. The economic system was one of old local networks of exchange. Your customer might be the one you sat next to in church or even a distant cousin you had known for decades. The economy was principally one of face-to-face contact. Business then was predominantly conducted with the use of the local German dialect in much of Northampton County outside of the English town of Easton. With some exceptions, such an insular environment prevented much intermingling with their English neighbors to the south. This would change considerably after about 1820 or 1830.

As the years rolled by, the manufacturing processes in the post-1820 era increasingly employed water-driven machinery and continuous production that resulted in precision-cut standardized components that some historians have referred to as “the American System.” The dominant theme then became that of an ever greater faceless society, the manufacturer often not knowing whom the product went to that he created, or even exactly when. The document that we have just looked at is an invaluable record of pre-Industrial–era lives of Northampton County residents that were soon to be changed in a vastly different economic environment that was about to manifest its pervasive effects just a few years down the road.

by Greg Huber

(This article was published in Fall 2013 LMTHS Newsletter)

Within the archives of the Lehigh County Historical Society is a document called “Manufactures.” The number of occupations listed reflects a countywide economy that concerned itself essentially with local markets. The products manufactured then tell of a local populace that was thriving in the very early part of the nineteenth century.

This was the era just before the advent of what historians have called the “market revolution” in the 1815 to 1840 timeframe. The 1810 list bespeaks a time when people in our area were producing goods using hand-forged tools in time-honored fashions since the mid-eighteenth century.

The list of trades and crafts is far beyond the commonly known occupations of farming, milling, masonry and weaving. Hundreds of people in the county then worked in a number of areas of employment. In earning their livelihoods, they formed an important part of the vast network of people working for and attending to the needs and desires of county residents. The list is not complete: a number of manufacturing occupations are not listed in the 1810 list, but can be found in, for example, early tax lists from Allentown. A surprising omission is the then-famous gun works in Jacobsburg.

The document is part of the population census of 1810 in Northampton County. This was two years before the western part of the county broke off and became Lehigh County in March 1812. The census consists of several pages of information, including areas of production called “manufac-tures,” with proprietors’ names, the amount of product of each activity, and the amount of money each proprietor made in the year 1810. All nineteen occupations are listed below, with the numbers of each and the total quantity of the product created by all the proprietors in each category, along with a few comments. The total number of proprietors was 318. Farming was not included. The number of farmers was likely in the thousands.

Grist Mills – 63 – 6,850 barrels of flower (flour) and 250,000 bushels of grain. Wheat flour was a cash crop for farmers. In 1810 the most common financial arrangement farmers had with millers was to pay for the miller’s work with a portion of the milled grain. A few gristmills built before 1810 in the area retain at least some of their original machinery. In Lower Macungie, the 1806 Kohler mill on Farr Road is an example.

Saw Mills – 27 – 970,000 feet of board and scantling. (Scantling is small timber used in construction.) Most timber processed by the sawmills originated from first-growth or virgin forests in the greater Northampton County area. Some may have come from secondary-growth sources or also perhaps from sources outside the county.

Paper Mills – 1 – 1,200 rheams (reams) of paper. A ream contained 480 sheets of paper then.

Oil Mills – 4 – 3,000 gallons of linseed oil – Linseed oil is a yellow oil extracted from the seeds of flax and used in paints and varnishes. It is possible that David Deschler’s stone structure on Orchard Place in Lower Macungie, known later as Seem’s Mill, was built as an oil mill. Another oil mill of eighteenth-century vintage was on Mill Race Road in Lower Macungie behind the 1832 Neumeyer grist mill.

Fulling Mills – 1 – unknown product quantity. Fulling is a water-intensive step in making cloth. It involves cleansing woven woolen cloth to eliminate oils, dirt, and other impurities, then pounding the fabric. The process shrank the fabric and made it thicker and softer.

Carding Machines by Water – 6 – 15,625 units of wool. Carding was a process by which fibers were opened, cleaned, and straightened in preparation for spinning. Modern carding dates from the use of revolving cylinders patented in 1748. Much carding would still have been done using hand tools in the home, and was not included in the industrial category.

Trip-hammers – 1 – 30 tons of iron. A trip hammer is a massive, usually water-powered hammer. The use of this one was not specified.

Distilleries – 100 – 105,170 gallons of rye and apple whiskey. It is not surprising that distilleries are by far the most numerous manufacture on this list. David Schmoyer is known to have operated an applejack distillery in Lower Macungie near Spring Creek and Route 100 from 1799 to 1801.

Tobacco factories – 6 – 30 tons of tobacco. Snuff, cigars and smoking and chewing tobacco were popular products at the time.

Potteries – 3 – unknown quantity. Local clays were used to make earthenware items in potteries.

Weavers – 45 – 70 looms and 47,000 yards of product. The list does not specify the type of cloth made. Some would have been linen, and some wool. Most farmers in Northampton County raised sheep for wool and meat, and grew flax, from which linen is made. Linen was used for fine textiles, work clothing and sacking. It was often used as the warp thread with wool as the weft thread to produce a strong, warm fabric.

Smitheries – 22 – 56½ tons of iron. Of all the manufactures listed here, the work of the smith was likely the most important as all farmers and probably all of the other occupations ultimately depended on the smith. Smiths made and repaired iron tools and farm and household implements of every description, and shoed horses.

Bluedyers – 3 – unknown quantity. Today these would simply be called dyers. Thread was usually dyed before being woven, using natural dyes derived primarily from plants.

Printing Offices – 1 – used 300 rheams (reams) of paper.

Hatters – 6 – 1,750 wool and 1,120 furr (fur) hats. Hatters made, sold and repaired hats.

Blast Furnace – 1 – 300 tons of iron – Hampton Furnace was built in 1809 in Upper Milford Township. It was a charcoal-fueled furnace.

Saddlers – 3 – unknown quantity. Saddlers made not only saddles for riding horses, but any kind of harness needed on farms and in towns.

Shoemakers – 20 – about 380 pairs of boots and 4,400 pairs of shoes. Most families made their own shoes.

Lime kilns – 5 – 12,000 bushels of lime. See pages 104–107 of A History of Lower Macungie Township. Burnt lime was used in construction, and was spread on fields. The five lime kilns listed were most likely large operations that provided construction material. Most farms in the limestone valley had a small lime kiln for their own use. Large commercial kilns were built later; one row may still be seen at Lower Macungie Township’s Camp Olympic Park.

Population

The 1810 document includes the population of residents of various townships in Northampton County. After Whitehall Township (which then included today’s Whitehall, South Whitehall and North Whitehall), the most densely populated area in all of Northampton County was Macungy Township. The census accounted for free white males and free white females. The total population for Macungy then was 2,431 males and females; one slave was listed, associated with the name of Reverend Jacob Van Buskirk, pastor of Lehigh (Zion’s) Lutheran Church in Lower Macungie. Van Buskirk owned a tannery in Macungie, which he founded in the mid-1780s.

All the occupations listed above are not found in all of the townships. Based on the extensive population of Macungy in 1810, the township had to have included at least six of the occupations. They include gristmills, saw mills, distilleries, weavers, smitheries and shoemakers. One tannery existed but was not listed. Residents of the township also pursued other occupations.

One interesting case of an occupation assigned to an individual but lacking a designation to a place of residency is that of John Romich. His name is listed as a gristmill owner. He produced 10,000 bushels. Romich was more successful (produced more bushels) than 60 of the 63 listed gristmill owners. A strong indication that this Romich family member occupied an area in Macungy is the mention of Romig’s Mill in A History of Lower Macungie Township (page 133), which states that “the locale surrounding the mill was once so thick with Romigs that for many years it was known as ‘Romig’s settlement.’ ”

Summary

The manufactures list of 1810 proves that many occupations existed in Northampton County at the end of the first decade of the nineteenth century. The structures themselves, unfortunately, associated with most of the manufactures have disappeared from the landscape. Exceptions include a few grist mills including the 1806 Kohler mill in Lower Macungie and a few lime kilns scattered about the countryside. In addition, several of the buildings in the Moravian industrial quarter established in the eighteenth century along the Monocacy still stand; they were presumably included in the tallies.

In 1810, the then prevailing technologies of production created hand crafted, non-standardized consumer goods. The economic system was one of old local networks of exchange. Your customer might be the one you sat next to in church or even a distant cousin you had known for decades. The economy was principally one of face-to-face contact. Business then was predominantly conducted with the use of the local German dialect in much of Northampton County outside of the English town of Easton. With some exceptions, such an insular environment prevented much intermingling with their English neighbors to the south. This would change considerably after about 1820 or 1830.

As the years rolled by, the manufacturing processes in the post-1820 era increasingly employed water-driven machinery and continuous production that resulted in precision-cut standardized components that some historians have referred to as “the American System.” The dominant theme then became that of an ever greater faceless society, the manufacturer often not knowing whom the product went to that he created, or even exactly when. The document that we have just looked at is an invaluable record of pre-Industrial–era lives of Northampton County residents that were soon to be changed in a vastly different economic environment that was about to manifest its pervasive effects just a few years down the road.